Act I:

Everything starts with a vision. When a child escapes a mother’s womb, he meets his first challenge: adjusting to a new world and facing the intensity of all new sensations. In the same way a human brain enters the world of mathematics when it discovers that universe for the first time. The most common answer I hear when people find out that I do math is, “Oh, I am so bad at math.” However, mathematics is the most beautiful, organized, and self-enclosed discipline I have experienced.

To develop love for that universe, one needs to be shown its beauty through its artistic side, through the visualization of its harmony. In this short blog post, I will share a simple computation and the corresponding visualization of rational numbers represented in a form slightly unfamiliar to non-mathematicians. This idea hit me suddenly while I was sitting in my apartment in Vancouver one night, and I spent the rest of that night playing around with some code and thinking about the beauty of rational numbers.

Act II:

The object of study today is a set of rational numbers, Q. There are two ways we can represent rational numbers. We can either think about them as the fraction p / q, with q being a non-zero natural number and p being an integer; or, we can think about them as the ordered pair (p, q), with the same p and q.

However, the points (p, q) and (2p, 2q) represent the same rational number p / q, as we can multiply its numerator and denominator by two, i.e., p / q = 2p / 2q. Therefore, for any non-zero integer r, the set of all points (rp, rq) represents the same fraction p / q where gcd(p, q) = 1 or -1, i.e., p and q do not have a common divisor except 1 or -1. Let us call a point (p , q) with gcd(p, q) = 1 or -1 a reduced point. And if |p| < |q| (|a| is an absolute value of a), then (p, q) is called a proper point. If 0<= p < q and gcd(p, q) = 1, then (p, q) is called a positive reduced proper point. In other words, we consider all rational numbers in the open interval (0, 1). Now we can assign a color to every rational number p / q by just taking its number p / q and using Python’s “jet” coloring scheme, where 0 is blue (cold) and 1 is red (hot). After this, we can color all positive reduced proper points in the same way. If we want to color any other point (n, m), then we need to construct a positive reduced proper point (n’, m’) from (n, m). In other words,

- find gcd(|n|,|m|) and set it equal to d,

- obtain a new point (|n|/d, |m|/d),

- if |n|/d > |m|/d, then find k such that |n|/d – k|m|/d < |m|/d,

- finally, set n’ = |n|/d – k|m|/d and m’ = |m|/d.

In other words, we make entries in (n, m) positive, and reduce all common factors of n and m; and if n is bigger than m, then we reduce n by multiples of m until what remains is less than m. In the end, we assign a color n’ / m’ to the point (n, m).

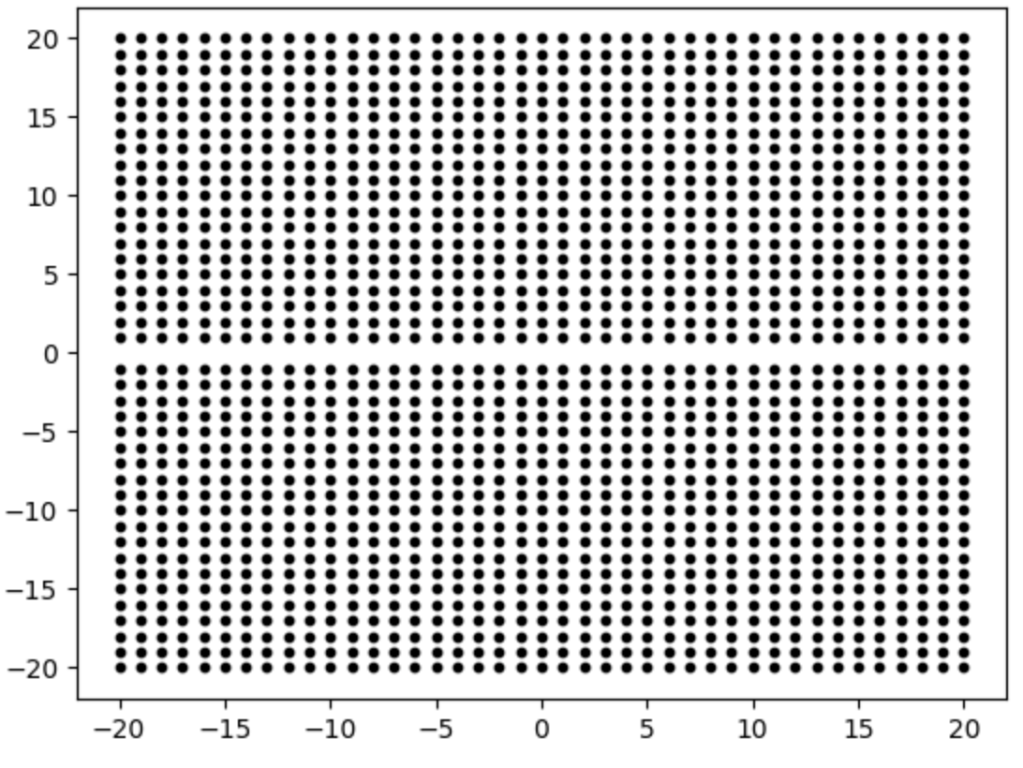

Let us right now follow the procedure above using some visualizations. First, we would generate 40 x 40 integer lattice without y-axis as it represents the denominator and cannot be zero.

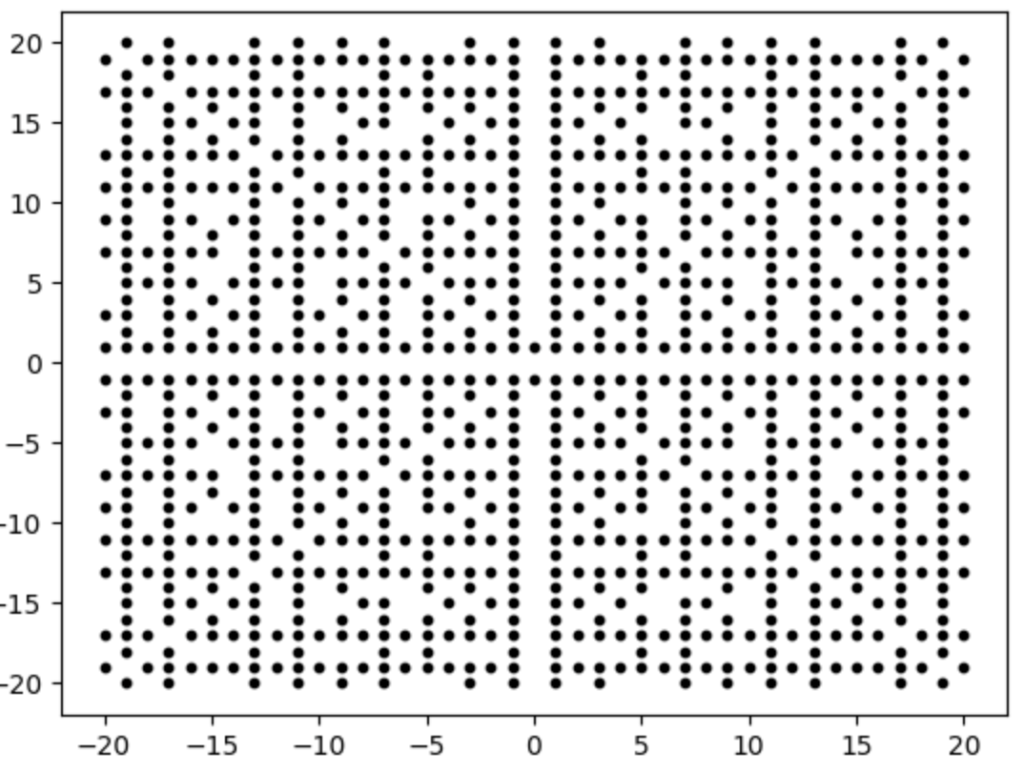

Next, we filter out all the points (n, m) that are not reduced.

After that, we take the set of positive reduced points (p, q) and assign to each a color according our rule, i.e., color(p, q) = p / q.

Finally, we will assign the color to every point in our lattice.

Act III:

I once heard one of the most important and influential sayings of my life: “It’s more important to solve one problem using multiple methods, rather than to solve multiple problems using the same method.” We can further reformulate this by saying: “It’s better to think about the same object from multiple perspectives, rather than to think about multiple objects from the same perspective.”

We have seen how we can represent rational numbers using two different constructions: as a subset of a real line and a subset of a real plane, where the first gives a better way to do computations and think about the rational numbers themselves. However, the second construction shows the richness and true color of rational numbers.

The best part, in my opinion, is that these two perspectives are united by the observer. You can obtain the first perspective if you imagine yourself standing at the end of the second perspective, looking towards the point (0,0).

How many other geometric perspectives, then, are there on the rational numbers?

Code:

The code is available via the link https://github.com/maxzubkov/rational_numbers.git

You can run it in Jupyter environment and Python.